Can humans perceive the benefits from modern exoskeletons?

One of the most active areas of investigation within the exoskeleton research field is how humans interact with these powered technologies. Within this lies the open question of how exactly we judge exoskeletons as successful. For context, we in the field have previously judged exoskeletons as successful if they reduce how many calories you burn during walking (metabolic cost reductions in the biz). The thinking goes that if the exo’s mechanical power substitutes in for some of your natural biomechanical power, it’s helped you. This is both pretty intuitive, as the less energy you expend, the longer/faster you could theoretically walk, and objectively measurable, as you can measure the reduction in metabolic cost.

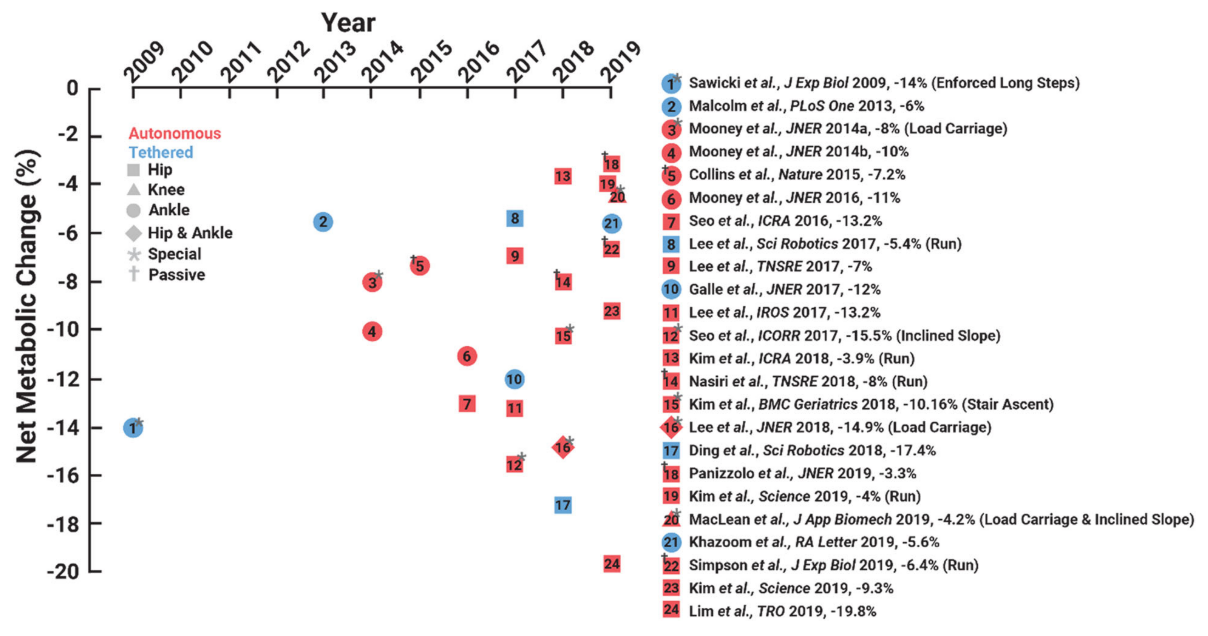

Using this metric, we’ve managed to obtain some pretty impressive reductions in metabolic cost using powered exoskeletons. The modern average is about a 14% reduction, with some exos even pushing 20%! Spurred by these successes, the field has focused almost exclusively on this metric of success, at the expense of most anything else.

Credit: Sawicki 2020

However, for all the great successes as a field in reducing the metabolic rate of the wearer, there’s been one key component missing in our analysis: can humans actually perceive these benefits? This is a pretty critical consideration, as if I just put an exoskeleton on you and you don’t feel that you’re being helped, will you actually choose to walk for longer? I think it’s pretty obvious you’d want to sense that you were being helped, i.e. you want to perceive the reduction in metabolics from the exoskeleton. This begs the question: just how perceptive are people to their metabolism?

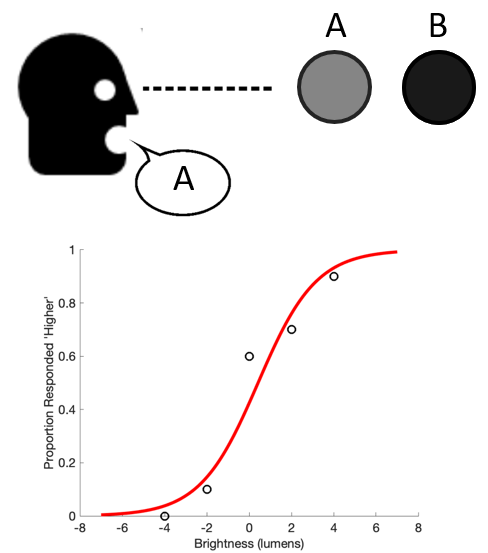

We can answer this question using the field of psychophysics, the science of perception. In psychophysics, we model the relation between some physical stimulus and human perception of that stimulus as following a sigmoid curve, typically a logistic curve, which we term the psychometric function.

At a high-level, the way you’d obtain this curve is by repeatedly asking a participant whether they sense a change in stimulus relative to some baseline. This is best illustrated using an example. Consider an experiment where we’re studying the perception of brightness. We’d show participants two circles of different brightness (measured in lumens). One circle, the reference, is kept constant, while the other circle, the comparison, changes in brightness across trials. The participant is then asked which of the two circles is brighter. We’d repeatedly poll the participant at different comparison brightness levels and obtain the proportions of times they responded the comparison was brighter than A. As you can imagine, the bigger the physical difference, the more accurate they’d be; conversely, as the circles get closer in brightness, the worse they’d be at distinguishing, down to the point that they’re basically just guessing. We’d then fit a psychometric curve that describes their performance using the data. This curve is somewhere between a perfect step, indicating perfect detection of even the smallest of physical changes, and a flat line, indicating pure unawareness.

An important quantity in psychophysics is the Just Noticeable Difference (JND), which is the perceptual threshold at which people are consistently able to determine that a physical change has occurred. In the field, we typically define ‘consistently‘ as 75% accuracy. The JND parametrizes the psychometric function, with smaller JNDs corresponding to steeper curves, and vice versa. The JND takes the units of whatever physical stimulus was used in the experiment, and is defined as the stimulus value corresponding to the point of 75% accuracy on the psychometric function.

The task is then clear: we find the JND of metabolic cost changes, which describes how perceptive people are to the benefits from exoskeletons.

We can use the Dephy ExoBoot to impose different metabolic costs on participants through varying the torque profile applied at the ankle. We impose sets of two metabolic costs back to back, and measure their actual metabolism via indirect calorimetry using the COSMED K5 breathing mask. Just like with the brightness example above, we then ask participants which of the two costs was higher, aggregate their responses, and obtain a psychometric function and JND.

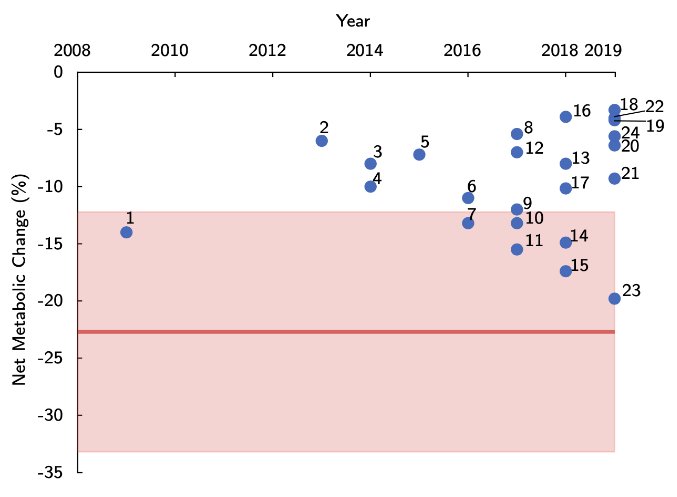

And here’s the psychometric functions and JNDs for the ten subjects in this experiment! The average JND was 22.7%, which is pretty high compared to other JNDs in psychophysics. This means that an exoskeleton would need to provide a metabolic benefit higher than 22.7% for you to sense that it helped you.

For context, here’s that graph from above of all the reductions in metabolism from modern exoskeletons (blue) with the thick red line denoting the JND. As you can see, none of the exoskeletons exceed this threshold, and thus would be imperceptible as beneficial by their users.

This was my first project as a PhD, and it represented a significant challenge. I had to crash-course psychophysics, learn how to use the COSMED, delve into the biomechanics literature, and develop a working controller for the ExoBoots. Overall though, I’m extremely satisfied with how it turned out! This was a critical question for the field to answer, as it informs that metabolism may not be the best metric of success if people don’t easily perceive the benefits from exos using this metric. The full paper is here if you’re interested. I think this opened up exciting new questions to answer, such as investigating what other metrics out there may be more impactful to their wearers.